I started using a Garmin Edge cycling computer in 2010. My Edge 705 served me well until 2016, when I upgraded to an Edge 1000. A design fault with the power button made me retire the Edge 1000 and start using an Edge 1030 in February 2018. A crash in July 2024 snapped one of the tabs on the quarter-turn mount interface on the underside of my Edge 1030. You can read about that adventure by clicking here.

I continued to use the 1030 despite it popping off the out-front mount whenever I hit a bump. The screen damage incurred during the same crash worsened progressively over the next two months. My son got me a good deal on an Edge 1050 in September 2024.

I very much like the Edge 1050.

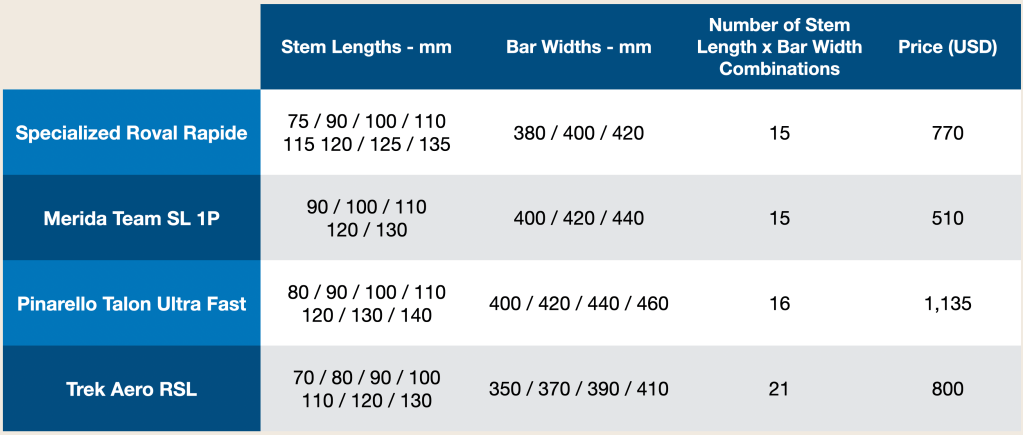

Each generation has progressively gotten larger and heavier. Interestingly, each generation is thinner than the previous one, which illustrates the increasing miniaturisation of components. The ever-larger width and height are due to the display size nearly doubling from the Edge 705 to the Edge 1030/1050.

The key improvements of the Edge 1050 over the Edge 1030 are the increased screen resolution and the switch from a transflective LCD to a transmissive LCD with a screen brightness of 1,000 nits. The Edge 1050 has a bright, high-resolution touch screen with more vivid colours.

| Specification | Edge 705 | Edge 1000 | Edge 1030 | Edge 1050 |

| Physical Dimensions (W × H × D) | 51mm × 109mm × 25mm | 58mm × 112mm × 20mm | 58mm × 114mm × 19mm | 60.2mm × 118.5mm × 16.3mm |

| Display Size (Diagonal) | 5.6 cm | 7.6 cm | 8.9 cm | 8.9 cm |

| Display Resolution (Pixels) | 176 × 220 | 240 × 400 | 282 × 470 | 480 × 800 |

| Weight | 104g | 114.5g | 124g | 161g |

There are also improvements inside the Edge 1050. Hardware changes include a much faster processor that delivers a smoother, more smartphone-like experience when scrolling, zooming maps, and navigating menus. The inclusion of Multi-band GNSS offers more precise tracking and positional accuracy. The basic beeper in previous devices has been replaced by a built-in speaker with an electronic bell and audio prompts.

Software improvements let you download and update maps via WiFi on the device and make contactless payments. There are hazard alerts and improved group-ride features. Lastly, the User Interface has been redesigned and is more responsive.

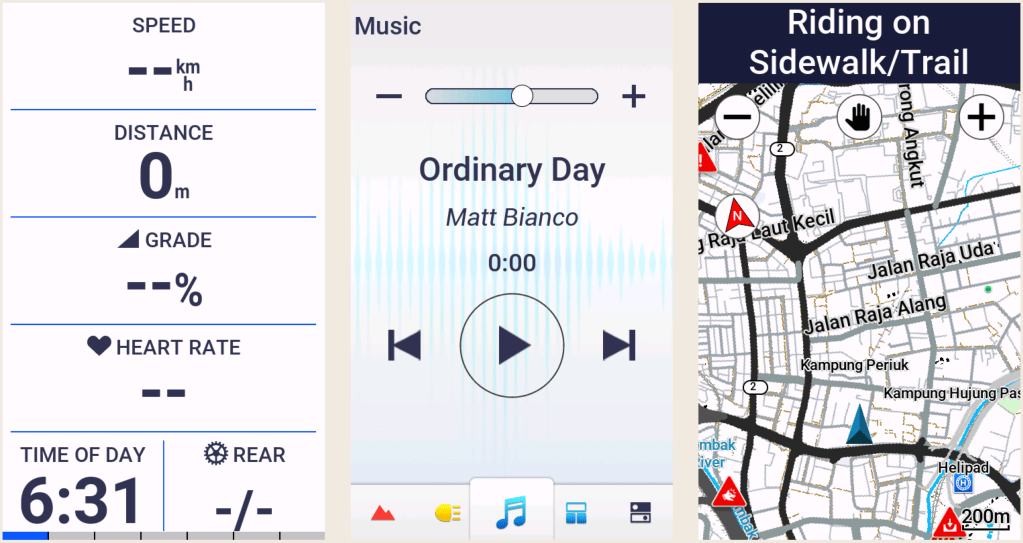

I progress through these three screens at the start of every ride. On the left is the Home screen that usually displays after the device has booted up.

In the centre is the Status widget screen. Widgets provide at-a-glance information like weather and notifications. Swiping down from the Home screen reveals the Widget screen. I usually turn on my Edge 1050 inside a car park. I use the Widget screen to confirm that my Edge 1050 has acquired a GPS satellite signal.

Touching the light icon at the bottom of the Widget screen reveals the Light screen. I control my Garmin Varia UT800 front light from the Light screen.

Swiping up from any Widget screen returns the display to the Home screen. From the Home screen, I can start a ride by touching the large ROAD activity profile button, start navigating by touching the NAVIGATION button, or access the system settings by touching the MENU button.

Touching the ROAD activity profile button goes to the data screen on the left below. Data screens, widget screens and activity profiles are all easily customisable. I have customised this screen to show the data fields I use the most.

I swipe left from my preferred data screen to reveal the Music screen. I ride with Shokz bone conduction headphones. The open-ear design lets me listen to music and navigation prompts without drowning out or masking the sounds around me. I can still hear a vehicle approaching me from behind and be in conversations while using the headohones.

I use the Music screen to control which track is playing and to adjust the playback volume.

I swipe right from the data screen to access the Map screen when I want to see the layout of the roads around me.

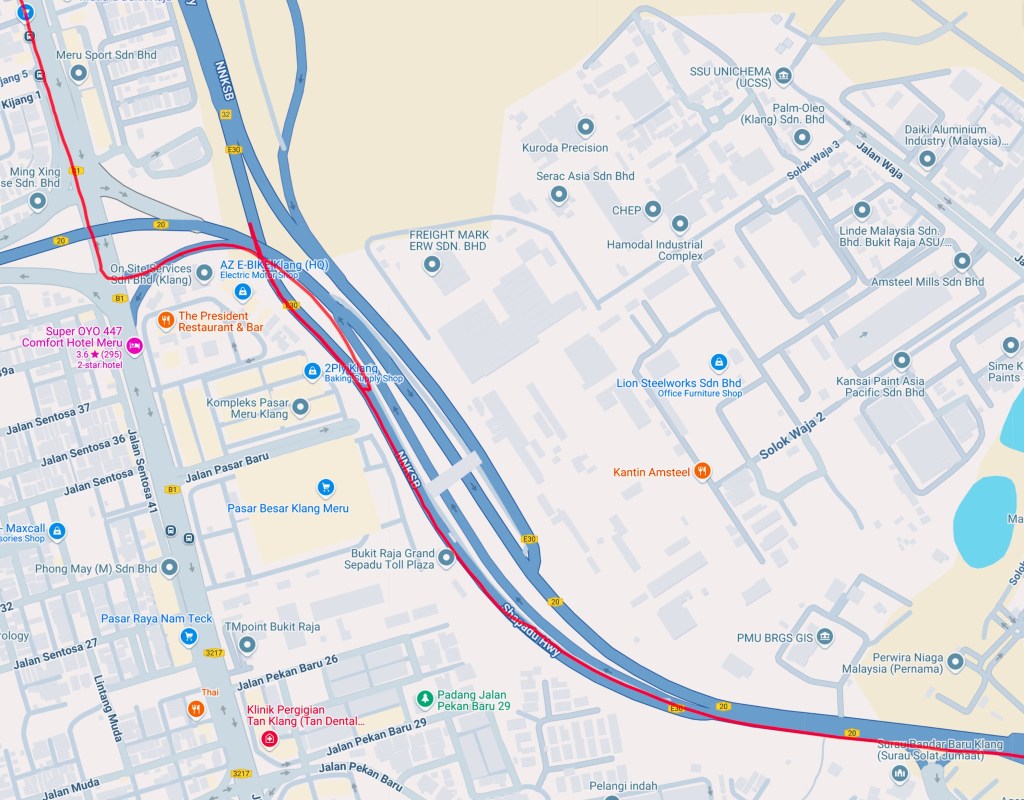

I often follow pre-loaded routes or courses that I created using the Route Planner on ridewithgps.com. I upload these custom courses wirelessly to my Edge 1050. The Map screen below is in navigation mode. The course is highlighted and a directional arrow is displayed.

If the navigation screen is not already displayed while following a course, it will pop up automatically about 100 metres before an upcoming turn.

The other two data screens display data fields that I occasionally refer to. I most often want to know the current temperature and how much climbing I have done.

I mentioned that the data screens are customisable. You can create up to 10 custom data screens for each activity profile on an Edge 1050. Each of these screens can be customised to display up to 10 data fields by default. While 100 data fields per activity profile sounds like a lot, Garmin provides 151 data fields to choose from, across the following categories, in alphabetical order:

| Data Type | Number of Fields | Examples |

| Cadence | 3 | Average cadence, Lap cadence |

| Cycling Dynamics | 19 | Time seated, Time standing |

| eBike | 5 | Assist mode, Travel range |

| Elevation | 12 | Average ascent velocity, Grade |

| Gears | 8 | Di2 shift mode, Gear ratio |

| Graphical | 13 | Graphs showing Current Power Zone, Current Cadence Range |

| Heart Rate | 17 | % of Heart Rate Reserve, Heart Rate Zone |

| Lights | 4 | Light mode, Battery status |

| MTB Performance | 6 | Grit, Lap flow |

| Navigation | 14 | Next waypoint, Time to destination |

| Other | 11 | Temperature, Number of laps completed |

| Power | 32 | current power output, Average left/right power balance |

| Smart Trainer | 1 | Trainer controls |

| Speed | 5 | Average speed, Lap speed |

| Stamina | 4 | Current remaining stamina, Remaining potential stamina |

| Timer | 7 | Elapsed Time, Lap Time |

| 1 | 12 | Distance to go, Step Distance |

The Edge 1050 is capable of much more than I use it for. I don’t use features like Event Adaptive Training, Livetrack, Cycling Dynamics, and Garmin Group Ride Radio.

The features I do use work very well. Heart rate tracking, turn-by-turn navigation, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi and ANT+ connectivity, and the built-in speaker.

The bell, which can be rung from the Timer overlay screen, is an appealing new feature. The initial implementation of this feature was a bit clunky. It required tapping the screen to view the timer overlay, and then tapping the Bell icon in the bottom right corner of the main menu. It often took a few pokes to accurately hit the Bell icon.

The latest software update simplifies ringing the bell. Now, double-tapping on any data screen rings the bell. Oddly, double-tapping does not work on widget screens. Nevertheless, a welcome improvement that fixes the only niggle I had with my Edge 1050.

The thing everyone wants to read about in a cycling computer review is battery life. The Edge 1050 has a claimed 20-hour battery life when used with sensors connected, navigation running, etc. This stretches out to 30 hours with the screen brightness lowered to about 20-30%.

Enabling Battery Saver Mode, which lets you reduce backlighting, hide the map screen and allow the device to enter sleep mode during an activity, extends the claimed battery life to about 70 hours.

I highly recommend the Edge 1050. Some may quibble over the size and weight of this device. I want a large, bright and high-resolution screen on my cycling computer. The Edge 1050 gives me that display in a package that weighs less than a McDonald’s Big Mac.

In closing, one feature of the Edge 1050 that I hope to never use is the replaceable quarter-turn mount interface. I would rather not hit another wild boar.