Slicing through the air like a speeding bullet. If only it were that easy for cyclists. Bullets are streamlined and aerodynamic, minimising their frontal area to reduce air resistance. A cyclist in a typical riding position has a much larger frontal area due to their body’s shape and size.

The power required to overcome aerodynamic drag on a bicycle increases with the cube of the speed. Doubling your speed requires eight times more power to overcome drag. This doesn’t account for other factors like friction and rolling resistance.

It is no wonder that reducing aerodynamic drag is such a big selling point for bicycle equipment designers and manufacturers. Many advertisements for bicycles and related gear claim wind tunnel testing shows power savings, measured in watts.

These advertisements sometimes do not tell you that the speeds commonly used in wind tunnel testing range between 40 and 48 kph (25 and 30 mph). The average reported ride speed on Strava for non-experienced cyclists is around 19.2 kph (11.9 mph). Experienced cyclists average 24.5 kph (15.2 mph). Recreational cyclists must temper their expectations of the number of watts they can save in real life.

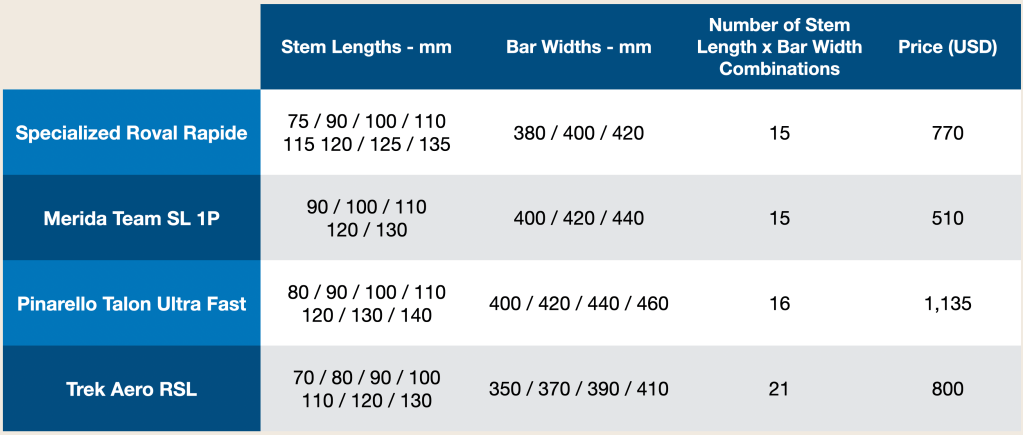

What gains can you expect from various aero upgrades? Absolute numbers vary from one source to another. The figures in the table below from BikeRadar are generally in line with others I have seen. The products in the table were tested in the wind tunnel at the Silverstone Sports Engineering Hub, a leading test facility for cycling in the UK. Testing was done at a range of yaw angles (0, +5 and +10 degrees) to get a more realistic picture of how these upgrades perform in the real world.

The bike used in the tests was a Specialized S-Works Aethos on 28c Continental GP5000 TL tires. The aero upgrades tested are identified below the product category.

The power savings at 35kph are minimal for most items. I would save even fewer watts on my rides, which rarely touch 35kph.

The rider contributes a large portion of the total aerodynamic drag on a bicycle, typically around 75-80%. So it is no surprise that the biggest aero gains come from changing body position. Moving the hands from the hoods to an ‘aero hoods’ position or using clip-on aero bars saves the most watts.

Many recreational cyclists struggle to hold either of these positions for long. Nevertheless, optimising body position is the most cost-effective aero upgrade.

The easier but more expensive route is to buy a set of aero wheels or even an aero bike. Just remember that the marketing around aero wheels and aero bikes is often a little over the top. By all means, spend money on a fancy new aero bike. But for many recreational cyclists to ride faster, losing weight and becoming more flexible to improve their body position will be more beneficial.