Participants in almost any sport can buy the equipment that the professionals use.

A Sunday league player can wear the same football boots as his or her top goal-scoring idol.

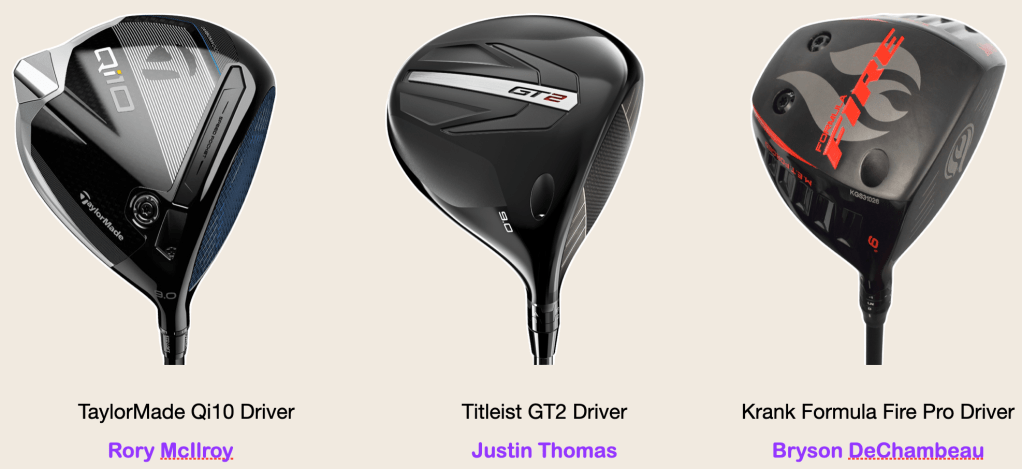

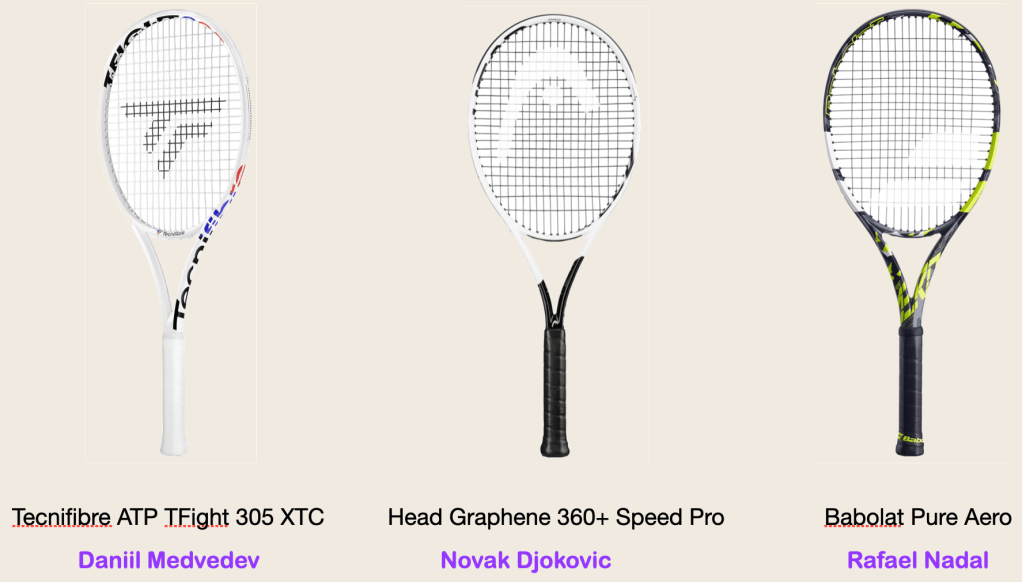

A duffer can tee off with the same club a PGA Major tournament winner uses to drive a golf ball 300 yards.

A recreational tennis player can serve double faults with the same tennis racquet an ATP Grand Slam winner uses to serve aces.

Apart from sizing considerations, there is little to stop amateurs from using the same equipment that the professionals in most sports use. No physical adaptation is needed to use such sports equipment.

This is not true of road bicycles. People often buy bicycles that they need to fit their bodies to, rather than bikes that fit their bodies.

There are lots of reasons why cyclists buy pro-level bicycles. Owning a high-end road bike can be a way to express personal identity or status, particularly within cycling communities, or to signal passion for cycling and commitment to performance. Some individuals may be drawn to the technical aspects of pro-level road bikes, including the components and frame materials. Others are attracted to these bikes because they are often beautifully designed and crafted.

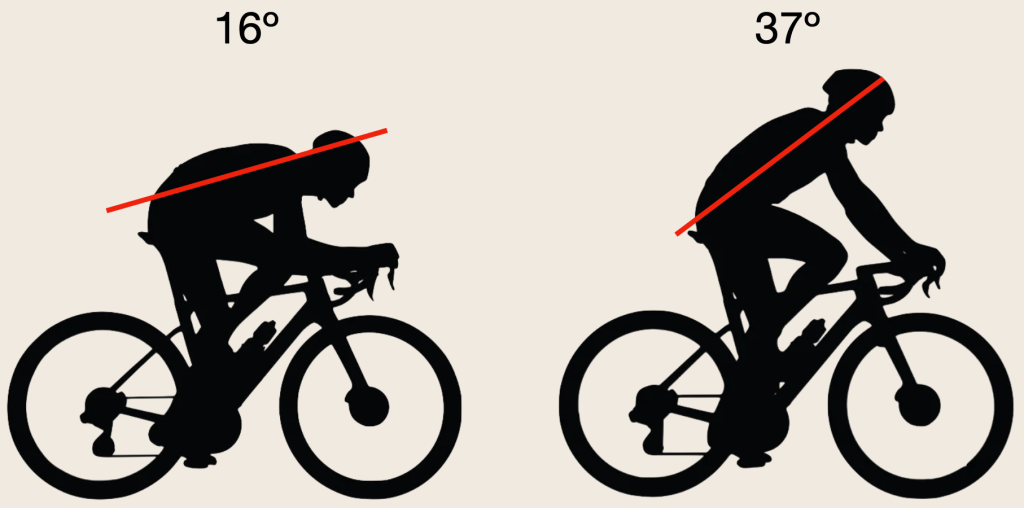

Unfortunately, riding a professional-level road bike is generally not recommended for amateurs. These bikes are designed for speed and efficiency, with a frame geometry that encourages an aggressive riding position. The handlebar and stem measurements of professional-level racing bicycles let the professional cyclist adopt an aggressive position that few recreational cyclists could endure for long.

The average male professional cyclist is 27.4 years old and weighs between 66 and 68 kilos. He has a high level of flexibility. He prioritises flexibility in hamstrings, hip flexors, and lower back, alongside areas like shoulders and chest, to counteract the typical low and long cycling posture essential to bike racing success.

The average recreational cyclist is older, has a belly which gets in the way of achieving an aggressive riding position, and is not very flexible. The result is that many amateur cyclists on high-end road bikes end their rides with one or more of these complaints: upper back pain, lower back pain, neck pain, aching shoulders and sore hands.

The main difference between the bicycles the professionals ride and the bicycles most of us mere mortals should be riding is in two frame measurements. These measurements are frame stack and frame reach.

Frame stack refers to the vertical distance between the centre of the bottom bracket and the top of the head tube, while frame reach refers to the horizontal distance between the same points.

A taller frame stack equals a higher handlebar. Bar height can be increased using headset spacers and a positive-angle stem, but it is always better to get a frame that fits you rather than adding headset spacers to a too-low frame.

The longer the frame reach, the further forward the handlebars will be. You can swap the 110 mm or 100 mm stem that road bikes typically ship with for a shorter stem to bring the handlebars closer to you, but this will compromise how the bike handles. Again, it is better to start with a frame that fits you.

The table below shows the frame stack and frame reach for professional-level race bikes and frames with more relaxed geometry from the same manufacturers. The more relaxed geometry frames are usually marketed as Endurance bikes.

The measurements are millimetres for frames that fit a 180 cm tall rider.

All the professional-level bicycles have a lower frame stack and/or a longer frame reach than the endurance bikes from the same manufacturer. The biggest differences are in the frame stack.

Despite the appeals of pro-level bicycles, the recreational rider would be wise to prioritise comfort over speed. That means foregoing the admittedly sexy pro-level race bikes in favour of a more forgiving endurance geometry.

Most recreational cyclists need a bicycle that allows them to adopt a more upright back angle than professional cyclists exhibit. In many cases, at least double the back angle. A taller frame stack and a shorter frame reach allow for a more upright position.

The main benefit for most recreational cyclists of owning a bicycle with a relaxed geometry instead of a race bicycle is greatly increased comfort. A secondary benefit is that an endurance bike is likely cheaper than a high-end race bike.

For happier cycling: Make your bicycle fit your body; don’t make your body fit your bicycle.